CHANEL Without a Face

By Thea Elle | February 17, 2026 | Luxury Industrial ComplexA family saga in three acts: talent, capital, and the quiet machinery that outlives them both.

It is tempting to tell CHANEL as a romance: a woman, a style, a perfume that changed the century.

But that story requires selective memory.

Gabrielle Chanel was at once a radical designer and a deeply compromised figure—social climber, opportunist, and, during the occupation, entangled with the Nazi apparatus she later tried to use for her own ends.

The truer story reads closer to Buddenbrooks with a Bloomberg terminal humming in the next room. Families, contracts, exile, a war, a return. And, underneath it all, a structure that converts desire into cash with almost indecent reliability.

This is a story about a name—and the people who owned the right to use it.

I. The arrangement (1924): authorship meets capital

When Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel turned her nose toward perfume, she was already a cultural force. But perfume was not a boutique trade; it was an industrial one. Bottling, distribution, advertising, global scaling—none of that lived in a couture salon.

Enter the brothers Pierre Wertheimer and Paul Wertheimer, heirs to Bourjois, a mass-market cosmetics company that understood how to sell dreams at scale. In 1924 they formed Parfums Chanel with Chanel and department-store impresario Théophile Bader. The split was brutally simple:

- Wertheimers: ~70%

- Bader: ~20%

- Chanel: ~10%

Chanel brought the myth and the formula. The Wertheimers brought the factory, the ships, the ad spend, the discipline. It was not romantic. It was effective. It separated authorship from ownership on day one.

And then the money started.

By the 1930s, Chanel No. 5 was a global hit. Chanel felt she had signed away too much. She sued, argued, maneuvered. The contracts held. The resentment didn’t.

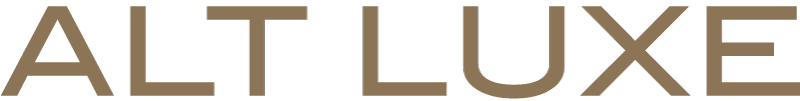

Coco Chanel: radical eye, ruthless instinct. She rewrote how women dressed—and spent the rest of her life trying to reclaim the business she had already given away.

II. War, exile, and a misjudged gambit (1940–1944)

War tests structures. It also reveals character.

The Wertheimers, who were Jewish, left France before the occupation and relocated operations to the United States. Anticipating Aryanization laws, they transferred control of Parfums CHANELto the non-Jewish industrialist Félix Amiot as a legal shield.

Chanel stayed in Paris. She entered a relationship with German officer Hans Günther von Dincklage and, in a decision that still stains the narrative, attempted to use Nazi racial laws to reclaim Parfums Chanel on the grounds that it was “Jewish-owned.” The maneuver failed. The legal protections held. The Wertheimers’ ownership survived the war intact.

After liberation, CHANEL was questioned but not prosecuted. Her reputation dimmed. She retreated.

Here is the dissonance that will never fully resolve: the house’s modern wealth engine endured because its owners fled, planned, and protected it—while its namesake tried to take it back through the very regime that made that protection necessary.

III. A return financed by the people she fought (1954)

In 1954, at seventy, CHANEL returned to fashion. It is often told as a heroic comeback. The financing rarely gets top billing.

The Wertheimers paid for it.

They underwrote the relaunch, absorbed early losses, and slowly consolidated full control of CHANEL’s commercial entities. CHANEL was compensated generously and supported for life. The adversaries became patrons. The business remained with the family.

After CHANEL’s death in 1971, the house drifted: fragrances and accessories printed money; fashion felt like an afterthought. Licensing proliferated. The brand’s cultural signal weakened. The cash flow did not.

This is the point most fashion histories glide past: CHANEL did not need fashion to survive. Fashion was optional. Perfume and leather goods were the engine.

In 1983, the third generation made the decision that rewrote perception: they hired Karl Lagerfeld.

Lagerfeld was prolific, theatrical, and—crucially—comfortable being an interpreter rather than an owner. He remixed codes from the 1920s and 50s into a machine for the late 20th century: camellias, chains, tweed, black-and-white, the interlocking Cs. He became the face. The family remained the structure. (He decoded the DNA of CHANEL and made, he was more a branding expert, or better genious, while he was a very creative person, I remember as a juicy bit, NY magazine editor on ece called him an overrated designer because

Ownership did not change. Equity did not change. Control did not change. What changed was the story people told themselves when they bought the bag.

Make an icon yours.

Shop Preloved Luxe now.

IV. The hire that reset the narrative (1983)

In 1983, the third generation made the decision that rewrote perception: they hired Karl Lagerfeld.

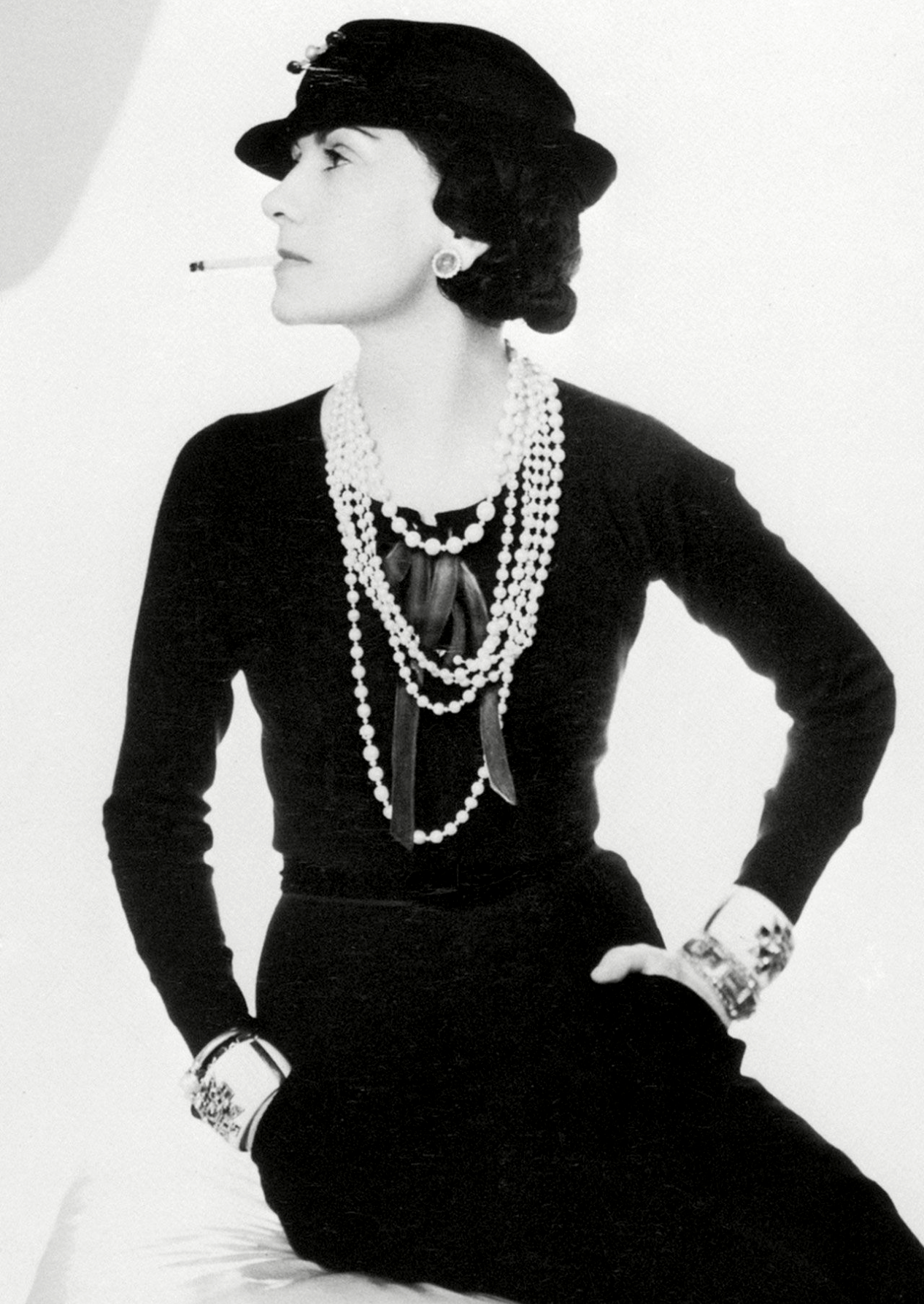

Lagerfeld was not a couturier in the purist sense. He did not build his legend cutting patterns in silence like Azzedine Alaïa, nor did he operate as a conceptual insurgent like Rei Kawakubo or Yohji Yamamoto. He did something more slippery and, in the end, more consequential: he decoded CHANEL as a language and treated it like a system of signs.

Camellia, chain, quilt, black-and-white, pearls, tweed, the double-C.

He didn’t invent them. He re-edited them—season after season, faster than anyone else in the industry could process—until they behaved like pop culture rather than heritage.

If Coco Chanel authored the alphabet, Lagerfeld wrote the daily newspaper.

This is why he confounded critics. Some argued—famously, sometimes bluntly—that he was “overrated” as a designer because he did not introduce a radically new silhouette. They were not entirely wrong. He was not trying to redraw the body. He was trying to program the brand.

Barbara Vinken called him, as early as the 1980s, a postmodern designer. That diagnosis has aged well. Lagerfeld treated CHANEL as a ready-made archive, sampling it, remixing it, amplifying it. He anticipated what fashion would become in the age of images: referential, fast, self-aware, endlessly recyclable.

And he understood something most designers resist admitting:

in a global luxury house, consistency is more valuable than originality.

He was also a character—sometimes dazzling, sometimes exasperating, often both in the same sentence. Lagerfeld’s wit was surgical and frequently reckless. He made enemies easily: critics, celebrities, public figures. His offhand comments about bodies, age, royalty, and politics triggered repeated outrage cycles, apologies, and non-apologies. He could be described—depending on who you asked—as a “petty dictator” running an empire of images, or as a brilliantly disciplined editor who knew exactly how far he could push before the system pushed back.

He liked aphorisms. He distrusted nostalgia. He once remarked that people like jeans because “you can wear them dirty”—a line that says more about his view of modern fashion than any manifesto.

Inside CHANEL, however, the arrangement was perfectly calibrated:

Lagerfeld had total visibility. The Wertheimers kept total control.

He became the house’s public intelligence—the voice, the silhouette, the daily proof that the brand was alive. They remained the infrastructure—the contracts, the capital, the continuity.

Ownership did not change. Equity did not change. Control did not change. What changed was the narrative velocity and the story people told themselves when they bought the bag.

V. The present tense: opacity as a strategy

Today, CHANEL is privately held by the Wertheimer family—primarily the brothers Alain Wertheimer and Gérard Wertheimer, descendants of Pierre and Paul. Revenues are widely estimated in the tens of billions annually; margins are enviable; the balance sheet is quiet.

No IPO. No activist investors. No quarterly theater.

The company publishes less than its peers. It explains less than its peers. It apologizes less than its peers. Silence, in this context, is not absence. It is policy.

The family’s personal lives mirror that stance. Alain, often described as media-averse, splits time between Europe and the U.S., and has long been associated with horse racing and breeding. Gérard is similarly private. The family’s philanthropic footprint exists—support for the arts, cultural institutions, and social causes through foundations and discreet patronage—but it is not performed as a brand campaign. Even their philanthropic style feels like the business: controlled, unadvertised, continuous.

It is difficult to turn that into a press narrative. It is even harder to turn it into a scandal.

Karl Lagerfeld, editor-in-chief of the archive. He didn’t invent CHANEL’s language—he remixed it into a global dialect: camellia, chain, tweed, double C. The codes stayed. The velocity changed.

VI. The house without a face

Fashion sells faces: founders, muses, designers, ambassadors. CHANEL, at street level, looks like faces everywhere—models, actresses, the ghost of Coco, the memory of Karl.

At the level that matters, it has none.

It has contracts. It has a family. It has a distribution system that learned how to sell one scent in 1924 and never forgot how to sell a feeling.

This is where ALT LUXE’s lens bites: the product is not design in the contemporary sense. The designs are almost a century old. The “designer bag” is a stabilized code—quilt, chain, clasp—iterated, protected, priced, and narrated. The creative lead interprets. The owners endure.

To call these objects “designer bags” is, strictly speaking, imprecise. They are licensed myths—heritage compressed into leather, priced as if time itself were scarce.

CHANEL to fashion is what global pop phenomena are to music—polished, scalable, instantly legible, engineered to travel. Craft is present. So is choreography. So is the system behind it.

Curated Finds. Timeless Style,

Thoughtfully. CRIS & COCO.

VII. The dissonance, without contempt

None of this requires condescension.

Coco Chanel’s instincts—about line, about comfort, about stripping ornament down to signal—were radical and lasting. The Wertheimers’ instincts—about scale, protection, patience—were equally radical in a different register. One produced a language. The other ensured the language would still be spoken, profitably, a century later.

There is betrayal in the story. There is opportunism. There is survival. There is grace, occasionally, and calculation, often. There is the moral fog of wartime choices that never fully clears. There is also a business that never needed to sell itself to survive.

Fashion likes to tell stories about genius and collapse. CHANEL offers a quieter proposition: continuity.

The house without a face: the men behind the structure. While the world looked at Coco and Karl, the Wertheimers kept the machinery intact—ownership, continuity, and the quiet discipline that outlives every silhouette.

VIII. What the money does (and doesn’t say)

With no outside shareholders, the family can decide what to do with profits without explaining it to anyone. Some of it returns to the business—retail architecture, ateliers, supply chains. Some of it flows into private investments. Some of it flows into philanthropy and the arts.

But there is no grand public performance of benevolence. No naming-rights spree. No quarterly ESG sermon. The money moves, but it does not narrate itself.

That is strange in a time when even charity is branded.

It is also, depending on your taste, admirable or unsettling.

IX. After Karl, still no face

Since Lagerfeld’s death in 2019, CHANEL has continued under creative leadership that treats the codes as a repertoire rather than a revolution. The house remains culturally visible and structurally unchanged.

The face changes. The structure does not.

X. Why this story resists the runway

Because it is not really about fashion.

It is about the difference between authorship and ownership, between image and infrastructure, between the story you buy and the system that sells it to you.

CHANEL perfected the split early, survived a war because of it, and never closed it again.

That is the architecture. The rest is styling.

Editorial Luxury Awaits